TLS: Secure Bytestreams

Secure Bytestreams

TCP by itself is insecure against network attackers. Someone on the network (e.g. a malicious router, an attacker sniffing packets on a wire) could read or even modify your TCP packets while they’re in transit.

Also, with TCP, you might connect to an attacker instead of the real server. Suppose you want to connect to a bank website, and you do a DNS lookup for www.bank.com. The attacker (e.g. someone who hacked into the resolver or a router) changes the DNS response so that it maps www.bank.com to the attacker’s IP address, 6.6.6.6. Now, when you form a TCP connection to the bank website, you’re talking to the attacker. You might end up sending your bank password to the attacker!

To address these security issues, we add a new protocol, Transport Layer Security (TLS), on top of TCP.

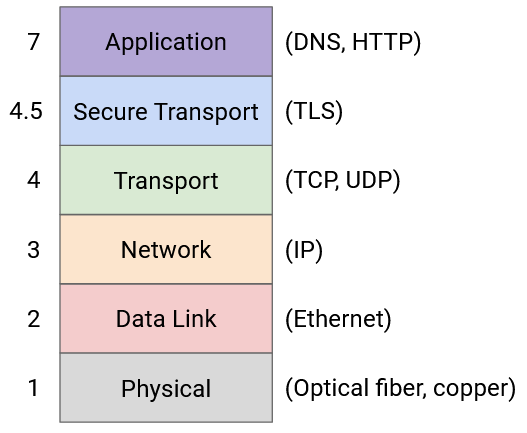

TLS can be thought of as a Layer 4.5 protocol, sitting in between TCP and application protocols like HTTP. (We use a weird number like 4.5 because the obsolete Layers 5 and 6 have nothing to do with security.) TLS relies on the bytestream abstraction of TCP, so it doesn’t think about individual packets or packet loss/reordering. TLS provides the exact same bytestream abstraction to applications as TCP does, but the bytestream is now secure against network attackers. This is why HTTP and HTTPS are semantically identical protocols. The only difference is that HTTPS runs over the secure bytestream of TLS-over-TCP, while HTTP runs over raw TCP with no TLS.

To distinguish between HTTPS and HTTP, we use Port 80 for HTTP connections, and Port 443 for HTTPS connections. Servers can force users to use HTTPS by replying to all Port 80 requests with a redirect to use Port 443 instead.

TLS Handshake

At a high level, TLS uses cryptography to encrypt messages sent over the bytestream. TLS also uses other cryptographic protocols (message authentication codes) to prevent attackers from changing messages as they’re sent over the network.

In order to encrypt traffic, TLS must start with an additional handshake to exchange keys and verify the identity of the server (e.g. real bank, not someone impersonating the bank).

Because TLS is built on top of TCP, the TCP three-way handshake first proceeds as normal. This creates an (insecure) bytestream, allowing all future messages, including the TLS handshake, to proceed without thinking about individual packets.

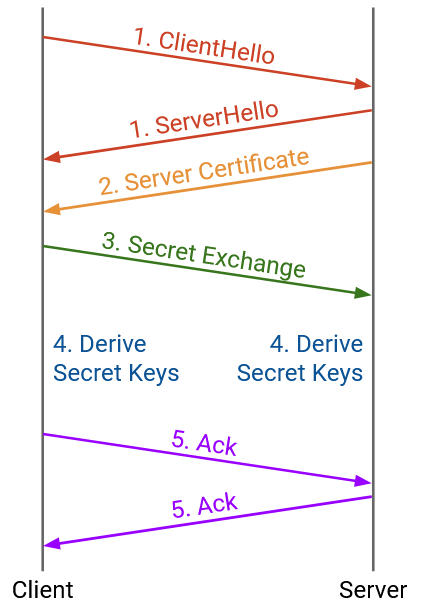

The TLS handshake can now proceed:

-

The client and server exchange hellos. The hellos contain random numbers, which ensures that every handshake results in different secret keys. (It would be bad if we used the same key every time, and attackers hacked us and learned that key.) The hellos also allow the client and server to agree on specific cryptographic protocols to use. The client’s hello lists all cryptographic schemes the client supports, and the server’s hello picks one to use.

-

The server sends a certificate of authenticity. This will allow the client to verify that it’s talking to the real server, and not an impersonator. There’s a bit of complexity in how the client actually verifies this certificate, which we won’t discuss here.

-

The client and server derive a secret that only the two of them know. Since the bytestream is still insecure at this point, they’ll need a cryptographic protocol that enables sharing a secret over an insecure channel. We won’t discuss the details here, but if you’re familiar with RSA public-key encryption (e.g. from CS 70 at UC Berkeley), that’s one possible cryptographic scheme to use here. The client encrypts a secret with the server’s public key and sends it to the server. Only the server knows the corresponding private key and is able to decrypt the message and learn the secret.

-

The client and server derive secret keys based on the shared secret and the random values from the hellos. Using the secret ensures that attackers can’t learn the secret keys. Using the random values ensures that we derive a different key every time. This derivation is done locally and independently by both the client and server. The secret keys are never actually sent across the network, so the attacker has no chance to learn them.

-

The client and server exchange some acknowledgements to confirm that they derived the same secrets, and nobody tampered with the messages sent over the network so far (since the bytestream is still insecure).

At this point, the handshake is complete, and all future messages are encrypted with the secret key (message authentication codes are also used to prevent tampering). We have now established a secure bytestream on top of the TCP connection, and applications can exchange data on top of our secure bytestream.