DHCP: Joining Networks

Joining Networks

When a computer first joins the network, what information does it need to connect to the Internet?

We always know our own MAC address, because it’s burned into the hardware.

We need to be allocated an IP address so we can send and receive packets. Recall, IP addresses are allocated geographically, so when we connect to a new network, someone has to give us an IP address to use.

We need to learn the subnet mask so that we can learn the range of local IP addresses. Given the mask (fixed bits all ones, unfixed bits all zeros), we can bitwise AND the mask with our own IP address to learn the local IP prefix.

We need to learn who the router on the local network is, so that we can send any non-local packets to the router. Sometimes we call this router the default gateway.

We also might need to learn where the DNS recursive resolver is located for this network.

The user could manually configure these values when they first join the network. This is time-consuming, especially since we have to re-configure these values every time we join a different network. Also, the average Internet user probably has no idea how to configure these values manually. That said, manual configuration does sometimes work for machines like routers, which don’t move around often.

We need an protocol that allows new hosts to automatically learn these values (and possibly other useful information).

DHCP: Dynamic Host Configuration Protocol

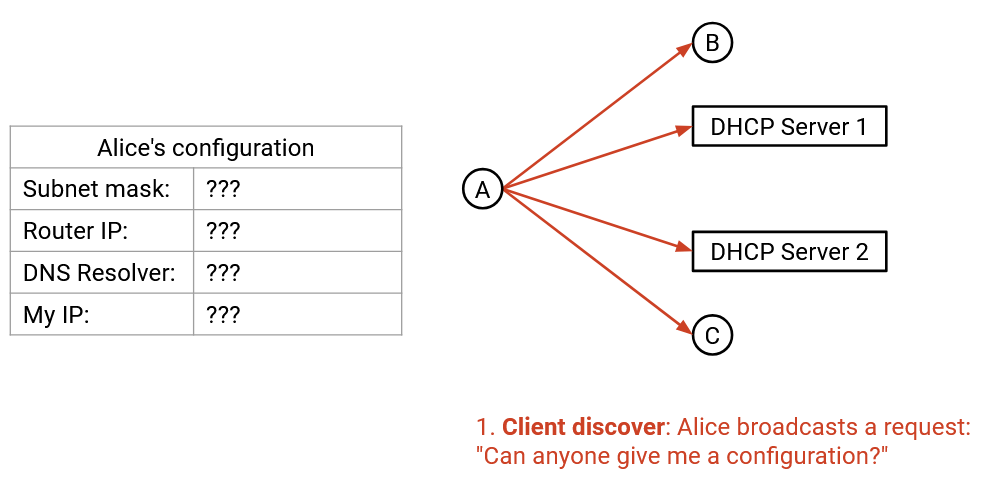

DHCP has four steps:

-

The new client broadcasts a Discover message, asking for configuration information.

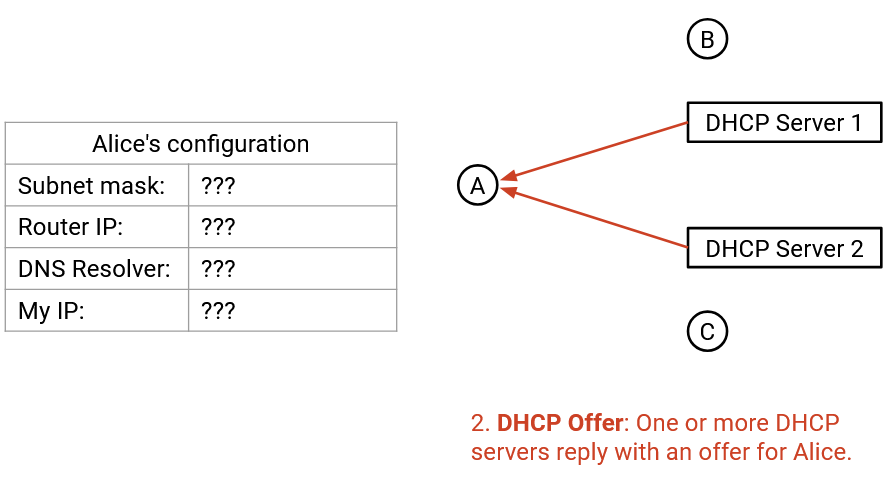

-

Any DHCP server who can help will unicast an Offer to the client, with a configuration that the client can use (e.g. IP address, gateway address, DNS address).

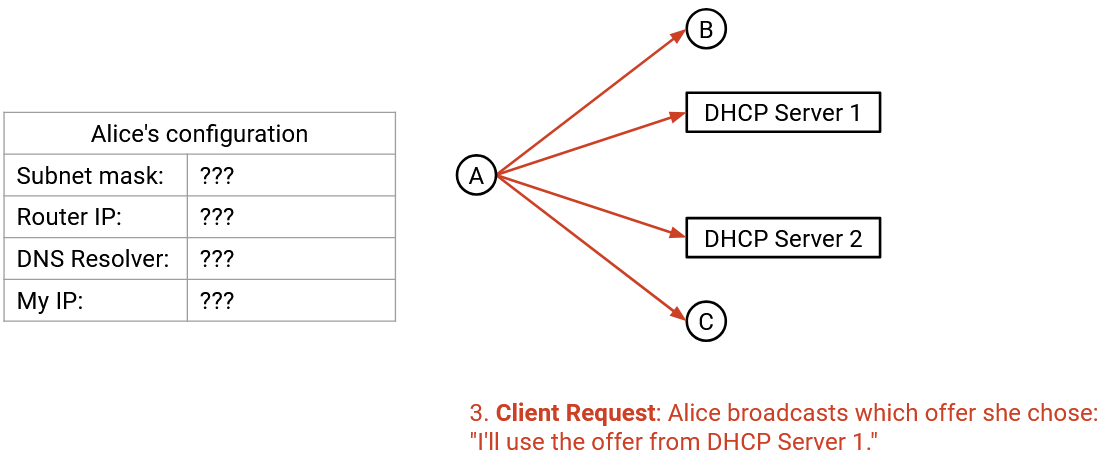

-

The client will broadcast a Request message, indicating which offer they accepted. This message is broadcast because the client might get multiple offers. By telling everybody which offer it’s accepting, the client allows the rejected offers to be freed up for future clients.

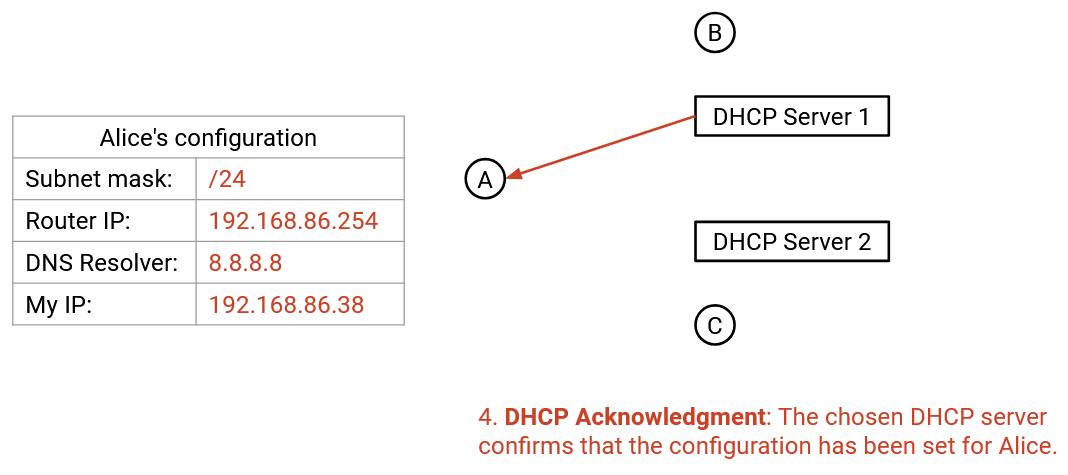

-

The server sends an acknowledgement to confirm that the request was granted.

DHCP Servers

In step 2, who is able to offer configurations? DHCP servers are added to the network, and their goal is to offer this information to new hosts. On smaller networks like your home network, the home router itself often acts as the DHCP server. In larger networks, there could be a separate machine that acts as the DHCP server.

DHCP servers need to be in the same local network as the client, since the protocol operates inside the local network. In larger networks, we might not want to run DHCP server code inside every router, so local routers can relay requests to a central remote DHCP server that actually runs the protocol.

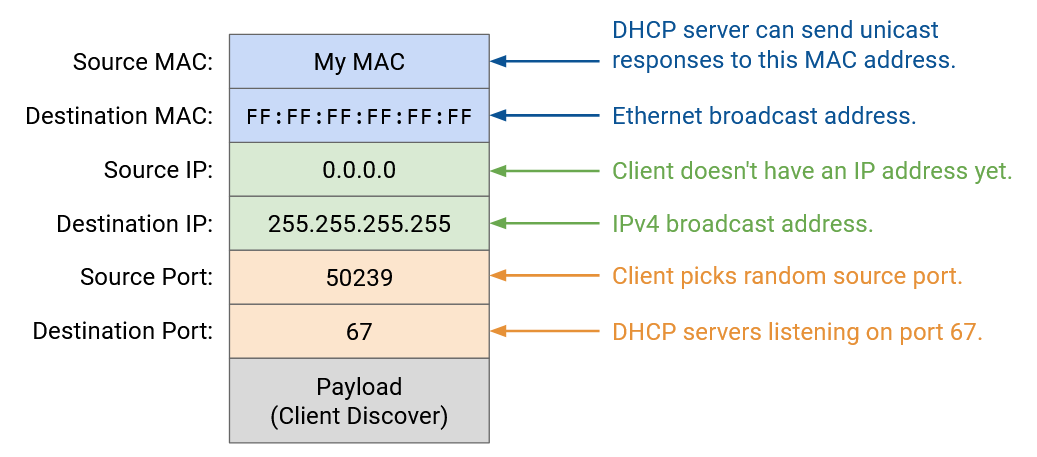

DHCP servers listen on a fixed port, UDP port 67, for requests from new machines. The servers are configured with all the necessary information: They know about the gateway and DNS servers, and they have a pool of usable IP addresses that they can allocate to new users.

Note that IP addresses are only temporarily leased to hosts. The lease is only valid for a limited amount of time (e.g. order of hours or days). If the host wants to keep using the address, it must renew the lease. If an IP address is currently leased to a host, the DHCP server cannot offer the same address to other clients.

DHCP Implementation

Note that DHCP is a Layer 7 application protocol, and it runs on top of UDP, which itself runs on top of IP.

In step 1, how does the client broadcast a message over IP? It sends a packet with destination IP of 255.255.255.255 (all ones), which is the IPv4 broadcast address. When this packet is passed down to Layer 2, instead of translating this IP address using ARP, the IPv4 broadcast address is mapped to the Ethernet broadcast address of FF:FF:FF:FF:FF:FF (all ones). Then, the packet can get broadcast across the network at Layer 2.

What about the source IP? The client doesn’t have one at the start of the protocol, so it sets the source IP to be 0.0.0.0.

With the hard-coded source IP of 0.0.0.0 and destination IP of 255.255.255.255, the client doesn’t need to know anything about the local network to start running this protocol.

If there’s no source IP, how do the DHCP servers know how to unicast the offers? The DHCP servers could either broadcast the offers, or use the client’s MAC address to unicast the offers.

Autoconfiguration in IPv6

DHCP also exists in IPv6 networks. However, because IPv6 addresses are longer, it turns out that we can give ourselves a guaranteed unique IPv6 address without anybody else managing a pool of addresses and leasing them. This protocol is called Stateless Address Autoconfiguration (SLAAC).

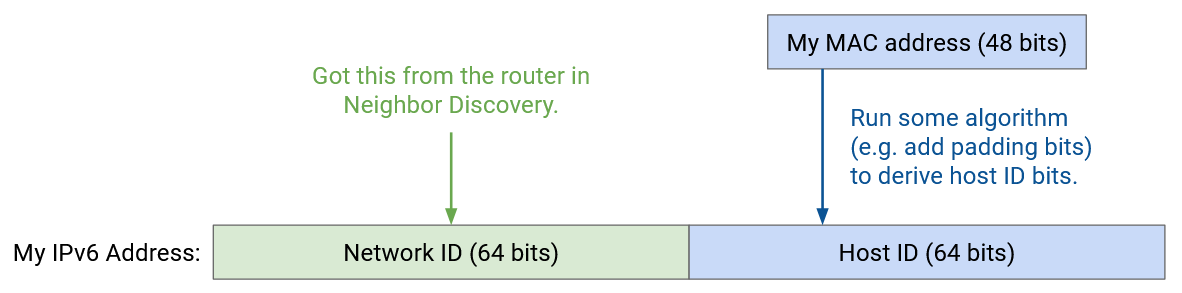

The trick is to use the MAC address, which we know is unique to each machine. As before, we ask for the local network information, which includes the gateway address, DNS address, and notably, the prefix for the local network. This prefix is usually 64 bits long. Then, we copy our own MAC address bits into the host bits of the IPv6 address. We can be confident that nobody else has this IPv6 address: users in other networks will have a different prefix, and no one else in the network (or anywhere else) will have the same MAC address bits.

To get the local network information, we can extend the Neighbor Discovery protocol (IPv6 version of ARP). The Router Solicitation message lets the user broadcast a request for the local network information, and the Router Advertisement message lets routers reply with that information.

SLAAC has additional mechanisms to detect duplicate addresses, just in case.